Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) Ophthalmology views the eyes as an extension of the body’s internal systems rather than isolated sensory organs. Vision is believed to reflect the functional state of key organs—particularly the Liver, Kidneys, Spleen, and Heart—and the proper circulation of Qi and Blood. From this perspective, eye symptoms often arise from systemic imbalance rather than purely local pathology.

In classical TCM theory, the eyes are closely associated with the Liver, which stores and regulates Blood. When Liver Blood is deficient or stagnant, symptoms such as blurred vision, dryness, floaters, or light sensitivity may occur. The Kidneys are thought to nourish deeper ocular structures, including the retina and optic nerve, through their role in storing Essence (Jing), making Kidney weakness traditionally linked to age-related and degenerative eye conditions.

The meridian system also plays a central role in TCM ophthalmology. Several meridians—including the Liver, Gallbladder, Bladder, and Stomach channels—either pass through or surround the eyes. Disruption of flow in these pathways is believed to impair nourishment and circulation to ocular tissues. Acupuncture and acupressure are commonly used to restore balance and support visual function.

Chinese herbal medicine is a cornerstone of TCM eye care. Herbal formulas are tailored to the individual’s pattern—such as Yin deficiency, Blood stasis, or internal heat—rather than a single diagnosis. Many herbs traditionally used for eye health have demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, circulatory, and neuroprotective properties in modern research. The foundations of TCM ophthalmology are described in classical texts such as the Huangdi Neijing, which emphasize prevention, individualized treatment, and restoring systemic harmony as the basis for maintaining healthy vision.

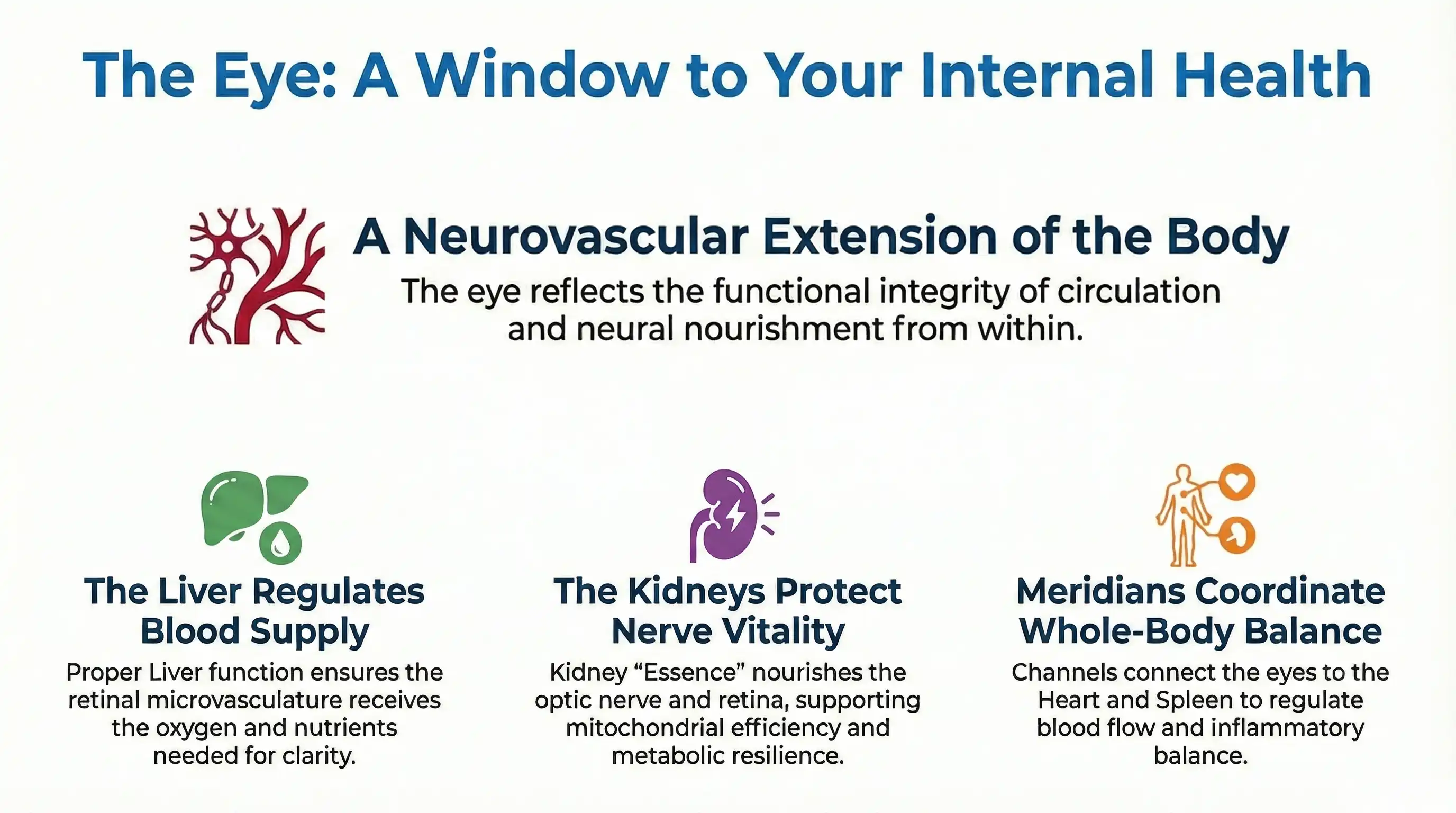

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), the eye is understood not as an isolated sensory organ but as a neurovascular extension of the body’s internal organs. Vision reflects the functional integrity of organ systems, circulation, and neural nourishment, making the eye a visible endpoint of deeper physiological processes. This concept closely parallels modern views of the retina and optic nerve as highly specialized neural tissue dependent on precise vascular regulation.

TCM theory emphasizes that the eyes are closely connected to the Liver,which stores and regulates Blood. Adequate Liver Blood ensures that the eyes receive sufficient nourishment to maintain clarity, endurance, and adaptability. When Blood supply is compromised, symptoms such as blurred vision, dryness, floaters, or visual fatigue may emerge. This mirrors modern recognition that retinal neurons rely on continuous oxygen and nutrient delivery through tightly regulated micro vasculature.

The Kidneys are believed to govern Essence (Jing), which supports growth, regeneration, and long-term vitality of the nervous system. In TCM, Kidney Essence nourishes the optic nerve and deep erretinal layers, linking age-related vision decline and neurodegenerative eye conditions to systemic depletion rather than local eye disease. This aligns with biomedical findings that optic nerve health depends on mitochondrial efficiency, axonal transport, and metabolic resilience.

TCM also describes the eye as integrated through meridian pathways that connect it to multiple organs, including the Heart, Spleen, and Gallbladder. These channels facilitate coordinated regulation of blood flow, neural signaling, and inflammatory balance. Classical sources such as the Huangdi Neijing describe the eye as a convergence point of vessels and channels, reinforcing the idea that vision reflects whole-body neurovascular health rather than isolated ocular structure.

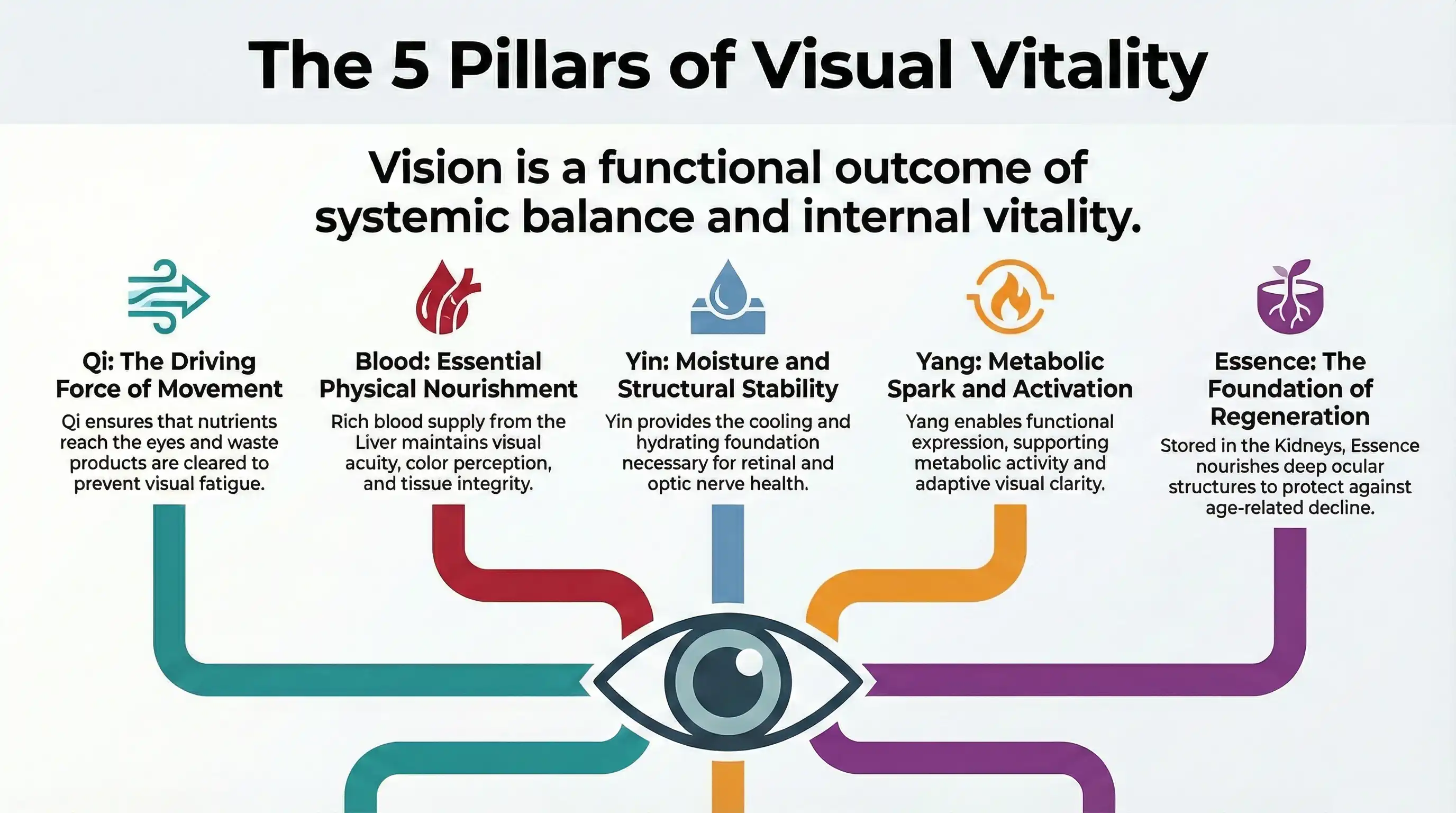

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), visual physiology is understood through the dynamic interplay of Qi, Blood, Yin, Yang, and Essence (Jing).These foundational concepts describe how the eyes are nourished, regulated, and sustained over time. Rather than focusing solely on anatomy, TCM explains vision as a functional outcome of systemic balance and internal vitality.

Qi and Ocular Function

Qi is the driving force of all physiological activity. In visual physiology, Qi governs movement, transformation, and regulation—ensuring that nutrients reach the eyes and waste products are cleared. Adequate Qi supports ocular muscle coordination, pupillary response, and adaptive visual function. When Qi is deficient or stagnant, visual fatigue, fluctuating clarity, pressure sensations, or transient blurring may occur, reflecting impaired functional regulation rather than structural damage.

Blood and Retinal Nourishment

Blood provides material nourishment to the eyes. TCM teaches that the eyes rely on a rich supply of Blood to maintain visual acuity, color perception, and tissue integrity. The Liver’s role in storing and regulating Blood is particularly emphasized. Blood deficiency or stasis is traditionally associated with symptoms such as dryness, floaters, dim vision, and difficulty seeing atnight. Healthy vision depends on both sufficient Blood volume and smooth circulation.

Yin and Structural Integrity

Yin represents cooling, moistening, and nourishing aspects of physiology. In the eyes, Yin maintains hydration, structural stability, and long-term cellular nourishment. Liver and Kidney Yin are especially important for retinal and optic nerve health. Yin deficiency may manifest as dry eyes, light sensitivity, burning sensations, or progressive degenerative changes—often worsening with age or overuse.

Yang and Ocular Functional Dynamics

Yang, by contrast, represents warmth, activation, and functional expression.Ocular Yang supports metabolic activity, visual responsiveness, and adaptive clarity. While Yin provides the substance of vision, Yang enables its expression. Imbalances—either deficient Yang or excessive Yang activity—can result in sluggish visual response or inflammatory symptoms such as redness, irritation, and pressure.

Low-Grade Chronic Ocular Inflammation

Dry AMD is characterized by persistent, low-grade inflammation within the RPE–Bruch’s membrane complex. Complement activation, microglial activation, and cytokine release create a chronic inflammatory environment that disrupts tissue repair, promotes extracellular deposits, and gradually weakens retinal support structures, contributing to slow but progressive macular damage.

Essence and Neurodegeneration

Essence (Jing) is the deepest and most fundamental substance in TCM, closely associated with growth, regeneration, and aging. Stored in the Kidneys, Essence is believed to nourish the brain, spinal cord, optic nerve, and retina. Decline in Essence is traditionally linked to progressive vision loss, reduced adaptability, and neurodegenerative eye cond itions. Unlike Qi and Blood, Essence is slowly replenished, making preservation and support critical in chronic visual disorders.

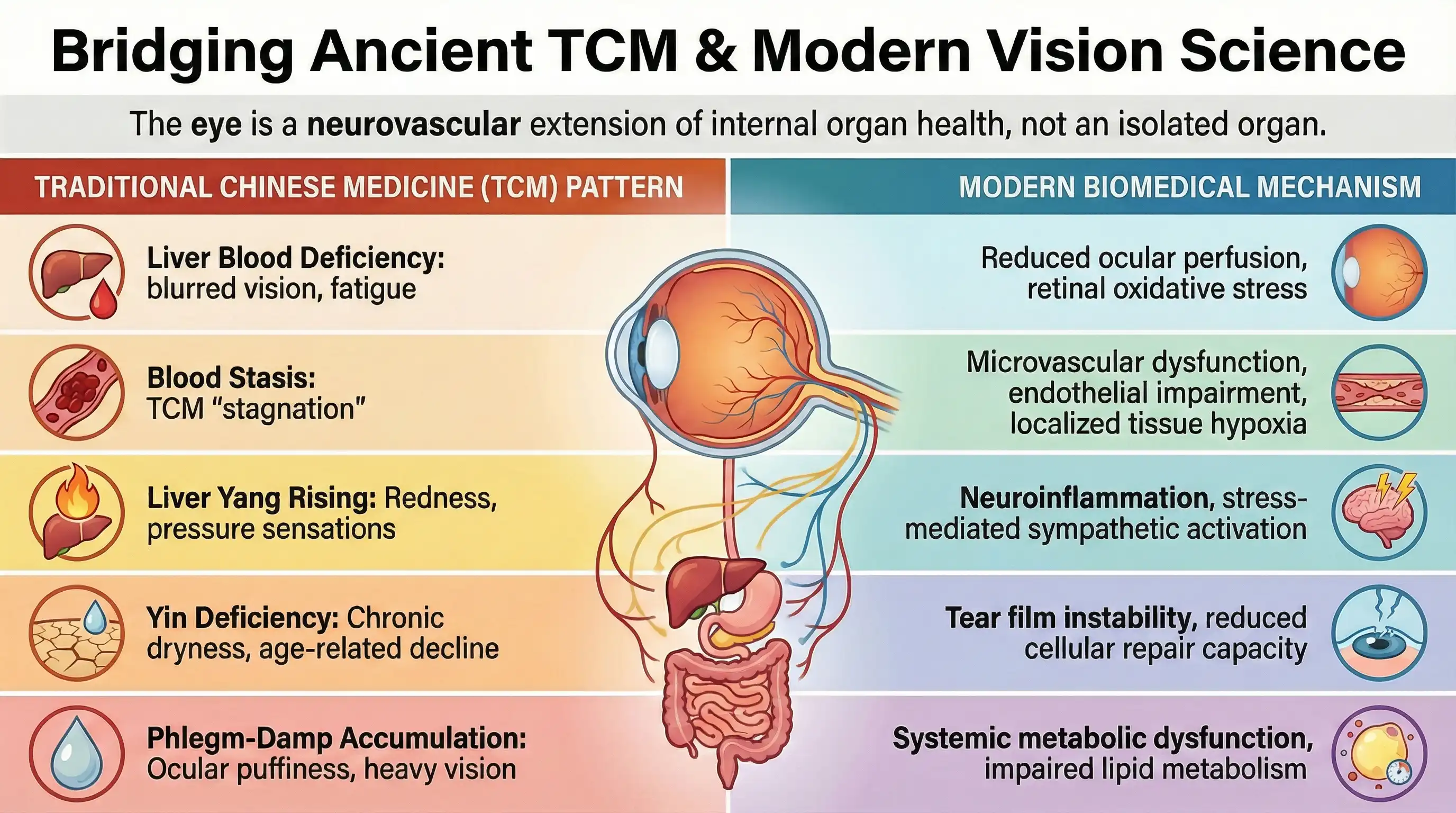

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) classifies eye disorders according to functional patterns rather than isolated anatomical diagnoses. These patterns reflect underlying systemic imbalances that influence ocular nourishment, circulation, inflammation, and neural integrity. When viewed through a modern biomedical lens, many of these classical patterns closely parallel recognized mechanisms in vision science, offering a meaningful bridge between traditional observation and contemporary physiology.

Liver Blood Deficiency

In TCM, the Liver stores Blood and supplies the eyes with nourishment necessary for visual clarity and endurance. Symptoms include blurred or dim vision, dryness, floaters, eye fatigue, and poor night vision. Biomedically, this pattern aligns with reduced ocular perfusion, diminished oxygen and nutrient delivery, mitochondrial inefficiency, and increased oxidative stress in retinal tissues. These factors are increasingly recognized in chronic visual fatigue and early degenerative eye conditions.

Blood Stasis

Blood stasis represents impaired circulation and stagnation. Clinically, it presents as persistent visual disturbances, fixed eye discomfort, dark circles, or symptoms that worsen with cold or inactivity.Modern correlates include microvascular dysfunction, endothelial impairment, altered blood rheology, and localized tissue hypoxia. Such mechanisms are implicated in optic nerve vulnerability, ischemic retinal stress, and progression of chronic eye diseases independent of intra ocular pressure.

Liver Yang Rising or Liver Heat

Liver Yang rising or Liver Heat is associated with red eyes, pressure sensations, headaches, light sensitivity, irritability, and stress-related symptom flares. From a biomedical perspective, this pattern maps to neuro vascular dysregulation, inflammatory cytokine activity, ocular surface inflammation, and heightened neural excitability. Stress-mediated sympathetic activation and vascular reactivity provide a plausible physiological basis forthese traditional observations.

Yang and Ocular Functional Dynamics

Yang, by contrast, represents warmth, activation, and functional expression.Ocular Yang supports metabolic activity, visual responsiveness, and adaptive clarity. While Yin provides the substance of vision, Yang enables its expression. Imbalances—either deficient Yang or excessive Yang activity—can result in sluggish visual response or inflammatory symptoms such as redness, irritation, and pressure.

Yin Deficiency

Yin deficiency, particularly of the Liver and Kidneys, reflects insufficient cooling, moistening, and regenerative capacity. Symptoms often include dry eyes, burning, glare sensitivity, and gradual visual decline, often worsening later in the day or with age. Biomedically, this pattern corresponds to tear film instability, meibomian gland dysfunction, increased oxidative damage, reduced cellular repair capacity, and age-related neurodegenerative processes affecting the retina and optic nerve.

Phlegm-Damp Accumulation

Phlegm-Damp accumulation, characterized by heaviness, blurred vision, fluctuating clarity, and ocular puffiness. Modern correlates include metabolic dysfunction, low-grade systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and impaired lipid metabolism, all of which can negatively influence retinal micro vasculature and inflammatory burden.

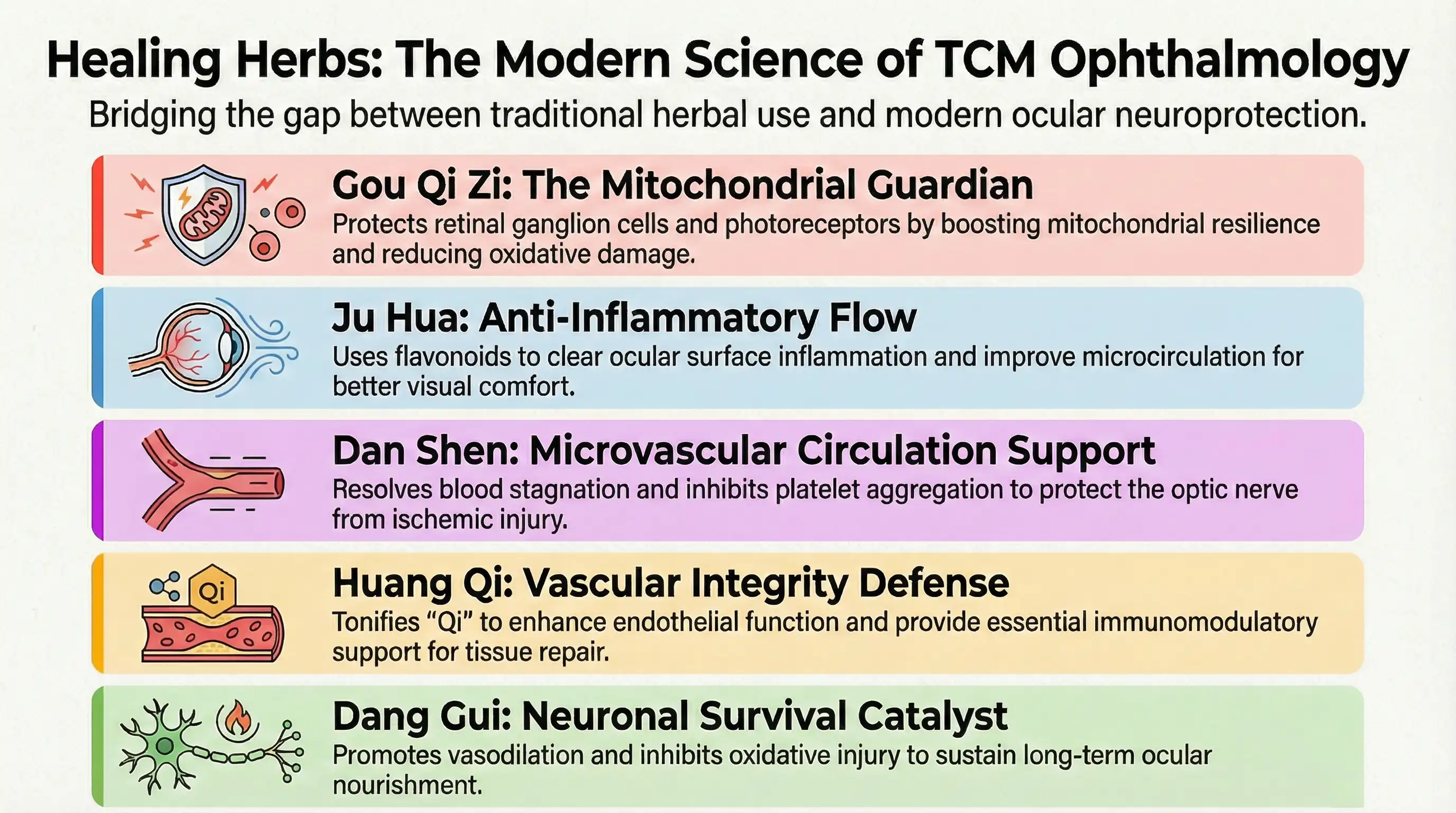

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has long employed medicinal herbs to support vision by restoring systemic balance and nourishing ocular tissues. Modern research has begun to clarify how many of these herbs exert measurable biological effects that align with contemporary understandings of ocular pathology, including oxidative stress, vascular dysregulation, inflammation and neuro-degeneration. Together, classical theory and modern science offer a complementary framework for understanding herbal mechanisms in eye health.

Gou Qi Zi

Gou Qi Zi (Lycium barbarum, goji berry) is one of the most widely recognized herbs for visual support. Traditionally used to nourish Liver and Kidney Yin, it is believed to enhance visual clarity and delay age-related decline. Modern studies show that Lycium polysaccharides possess strong antioxidant and neuroprotective properties, helping protect retinal ganglion cells and photoreceptors from oxidative damage. These compounds have also been shown to support mitochondrial function and reduce apoptosis in retinal tissue.

Ju Hua

Ju Hua (Chrysanthemum morifolium) is commonly used for eye strain, redness, and dryness. In TCM, it clears Liver heat and improves the smooth flow of Qi to the eyes. From a modern perspective, chrysanthemum contains flavonoids and phenolic compounds with anti-inflammatory and vasodilatory effects. These actions may help reduce ocular surface inflammation and improve microcirculation, supporting visual comfort and clarity.

Dan Shen

Dan Shen (Salvia miltiorrhiza) is traditionally prescribed to move Blood and resolve stagnation, particularly in chronic conditions. In ocular physiology, impaired blood flow and ischemia are increasingly recognized contributors to retinal and optic nerve damage. Modern research shows that Salvia compounds improve microvascular circulation, inhibit platelet aggregation, and reduce oxidative stress. These effects may help protect the retina and optic nerve from ischemic injury and chronic hypoxia.

Huang Qi

Huang Qi (Astragalus membranaceus) is used to tonify Qi and enhance systemic vitality. In eye health, strong Qi is believed to support circulation and tissue repair. Astragalus has demonstrated immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as the ability to support endothelial function. These effects are relevant in conditions where vascular integrity and immune-mediated inflammation contribute to ocular damage.

Dang Gui

Dang Gui (Angelica sinensis) plays a central role in nourishing and moving Blood. Traditionally associated with improving circulation and tissue nourishment, it is often included in formulas for chronic visual fatigue and degenerative conditions. Modern studies suggest that Angelica compounds promote vasodilation, inhibit oxidative injury, and support neuronal survival, aligning with its traditional use in sustaining ocular nourishment.

Bridging TCM pattern theory with modern vision science means translating TCM’s functional “patterns” into physiological themes that modern research already uses: perfusion, inflammation, oxidative stress, neurotrophic support, metabolism, and barrier integrity. TCM patterns aren’t the same as Western diagnoses. They’re clinical portraits—clusters of symptoms, triggers, tongue/pulse signs, and whole-body context—that guide individualized care. Modern vision science, meanwhile, classifies disease by anatomy and measurable pathology. The bridge is built when we treat patterns as hypotheses about underlying biological states.

“Liver Blood Deficiency” as ocular nourishment and neurovascular support

In TCM, the Liver “stores Blood” and the eyes rely on Blood for clarity and endurance. Modern parallels include inadequate microvascular delivery (oxygen, glucose), reduced mitochondrial efficiency, and insufficient trophic support for retinal cells. Patients who describe dry eyes, eye fatigue, dim vision, poor night vision, or floaters—especially with anemia-like fatigue or poor recovery—map plausibly onto states of compromised tissue nourishment plus elevated oxidative load.

“Blood Stasis” as microcirculatory dysfunction and endothelial stress

Blood stasis often presents with fixed or stabbing discomfort, chronicity, dark under-eye tone, headaches, or symptoms that worsen with cold or immobility. A modern lens would consider endothelial dysfunction, altered blood rheology, impaired autoregulation, and localized hypoxia—factors implicated in optic nerve vulnerability and retinal ischemic stress. This is less about a blocked artery and more about “micro-flow quality” and oxygen delivery.

“Liver Yang Rising / Liver Heat” as neuroinflammation, excitability and vascular reactivity

This pattern commonly includes red eyes, pressure sensation, light sensitivity, headaches, irritability, and symptoms worsened by stress or alcohol. Modern correlates can include inflammatory cytokine activity, ocular surface inflammation, trigeminal sensitization, and dysregulated vascular tone (too constricted or too reactive). The bridge here is recognizing that “heat” often tracks with inflammatory signaling and hyper-responsiveness, not just infection.

“Yin Deficiency” as barrier dryness, aging biology, and oxidative stress

Yin deficiency is characterized by dryness, burning, afternoon/evening worsening, heat sensations, insomnia, and gradual decline. In modern terms, think tear film instability, meibomian dysfunction, reduced mucin/lipid layer quality, and age-associated increases in oxidative stress with reduced repair capacity. It also aligns with chronic degenerative trajectories where inflammation is low-grade but persistent.

“Phlegm-Damp” as metabolic-inflammation overlap

Phlegm-damp patterns include heaviness, puffiness, mucus, brain fog, and sluggishness. In modern vision science, systemic metabolic dysfunction (insulin resistance, dyslipidemia) and chronic inflammatory tone can influence retinal microvasculature, oxidative stress burden, and ocular surface quality. This is where lifestyle inputs—sleep, diet quality, movement—often become the strongest shared intervention language.